Formats: Print, digital, audio

Publisher: Hellbound Books

Genre: Blood & Guts (Gorn), Monster, Myth and Folklore, Occult

Audience: Adult/Mature

Audience: Adult/Mature

Diversity: Gay author and gay side character

Takes Place in: US

Content Warnings: Animal Death, Body Shaming, Bullying, Child Endangerment, Death, Forced Captivity, Gaslighting, Gore, Mental Illness (depression), Physical Abuse, Sexual Assault, Self-Harm, Slut-Shaming, Suicidal Ideation, Violence (Highlight to view)

Blurb:

| Something is listening to the prayers of St. Paul’s United Church, but it’s not the god they asked for; it’s something much, much older. A quiet Sunday service turns into a living hell when this ancient entity descends upon the house of worship and claims the congregation for its own. The terrified churchgoers must now prove their loyalty to their new god by giving it one of their children or in two days time it will return and destroy them all. As fear rips the congregation apart, it becomes clear that if they’re to survive this untold horror, the faithful must become the faithless and enter into a battle against God itself. But as time runs out, they discover that true monsters come not from heaven or hell… ...they come from within. |

***

Angela and her son, Alex, have been the center of church gossip ever since her husband, Rick, vanished mysteriously. Seemingly tired of the pity and Emily's suspicious scorn Angela announces during Sunday service that she's planning on moving away and starting fresh. That's when a filthy Rick stumbles into the church. The congregation, who have been praying for his safe return, declares it a miracle. Angela, however, is less than thrilled. While the community sees the couple's relationship as the perfect romance, high school sweethearts who marry young and went on to have a child, nothing could be further from the truth. Rick is an abusive and violent man who terrorizes his wife, Angela was desperate to escape his cruelty and protect her son, and his time away has made him even worse. While gone, Rick has found a new god, the Behemoth, and has apparently started some sort of Cenobite-type religion that involves torture, murder, self-mutilation, and a very aggressive recruitment strategy. Everything starts to go to hell after that.

|

| At least I assume this is what Scientology is, but with more aliens and domestic espionage. |

On the Sunday of Rick's ill-fated return, the pastor, Don, tells his congregation about the myth of Job, a devout and righteous man whose faith is tested by hardship. For those unfamiliar with the parable, God and Satan aka "the Adversary" ("satan" literally translates to "adversary" so it's unclear whether this is big S Satan, aka the devil, or just some random angel who's a jerk) are hanging out in heaven and God is bragging about the super pious and awesome Job. Satan rolls his eyes and points out that Job is only "good" because he knows God blesses the righteous and punishes the wicked. He's doing it for the rewards, not out of some deep sense of morality. God suggest they test that theory and gives Satan permission to ruin Job's life by killing his servants and children, taking his wealth, and covering the poor man with boils. Job's so-called "friends" also subscribe to the theory that bad things only happen to bad people, and proceed to blame the victim by telling the poor man that all his misfortune is his own fault. At this point Job is pretty miserable and wondering what the hell he did to deserve this and demands to know why an all-powerful deity would make the world so chaotic and horrible. Surprisingly God actually responds with something along the lines of "Where the hell were you when I made earth out of literally nothing!? I made a freaking universe and you people don't even know what electricity is yet. Do you really think your stupid little monkey brain could understand all the complexities that go into running this place? I have all these plans you couldn't even wrap your brain around, like winning a bet with this guy... never mind, the point is: I'm omnipotent, omniscient, and I work in mysterious ways. Deal with it." Stunned, Job stammers out "Well, you didn't really answer my question, like, at all, but you're really scary and I don't want an all-powerful deity angry at me so I think I'm just going to go back to being pious and throw in some groveling apologies so you don't smite me." God says "Yeah, you do that" and restores Job's riches and health, and even gives him some new kids (because apparently children were easily replaced like goldfish back then), just so there are no hard feelings. The parable is meant to explain why good people suffer for seemingly no reason, though a more cynical interpretation would be that powerful beings treat mortals as mere pawns in their games and get unreasonably angry when those mortals want to know why they're acting like jerks. While God is ranting at Job for questioning his betters, the irritable deity starts not-so-humbly bragging about how powerful they are, using the Behemoth as an example. The Behemoth, an enormous, land-dwelling beast, is so powerful that it can only be controlled by God, no mortal could ever hope to defeat it.

“Behold now behemoth, which I made with thee; he eateth grass as an ox.

Lo now, his strength is in his loins, and his force is in the navel of his belly.

He moveth his tail like a cedar: the sinews of his stones are wrapped together.

His bones are as strong pieces of brass; his bones are like bars of iron.

He is the chief of the ways of God: he that made him can make his sword to approach unto him."

(Job 40: 15-19)

No, I don't know why God spends so much time telling Job about the Behemoth's giant genitals ("tail" was probably euphemism). Whomever wrote that particular bible story was having a really weird day. Jewish apocrypha describe the Behemoth as a primal creature that represents chaos and will battle with its aquatic and aerial counterparts, the Leviathan and Ziz, on judgement day.

The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis "Especially in its Western form, Christianity is the most anthropocentric religion the world has seen. Man shares, in great measure, God's transcendence of nature." Abrahamic all but declare humanity's superiority. In the very first book of the Torah and the Old Testament (Bereishith/Genesis) God essentially tells Adam that he is the most important living thing in the universe. "And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth." (Genesis 1:26) In the Quran, even divine beings are told to bow down before the first human. "And when We told the angels, 'Prostrate yourselves before Adam!' they all prostrated themselves, save Iblis, who refused and gloried in his arrogance: and thus he became one of those who deny the truth." (Surah 2:34) A relic from another time the creature's morality cannot be defined by human parameters, and has nothing to do with any human religion. The church members, who clearly subscribe to the idea of human exceptionalism, at least in the beginning, simply assume it does.(Job 40: 15-19)

No, I don't know why God spends so much time telling Job about the Behemoth's giant genitals ("tail" was probably euphemism). Whomever wrote that particular bible story was having a really weird day. Jewish apocrypha describe the Behemoth as a primal creature that represents chaos and will battle with its aquatic and aerial counterparts, the Leviathan and Ziz, on judgement day.

Unfortunately for the congregations, God never does show up to control the Behemoth. A few people try to stand up to the beast at first, but all are brutally killed for their efforts and the legend of Job offers little comfort to their grieving loved ones. Some of the church members begin to wonder if there is even someone out there listening to their prayers. Even if there is, a hands-off God who lets innocent people suffer and die quickly loses their appeal when the prehistoric monster terrorizing you can promise rewards now. As they become even more frightened and desperate every adult becomes complicit in some form of depraved cruelty, whether they are active participants or merely remain silent and allow it to happen. This begs the question, if you willingly do something unspeakable to save your own skin, is the life you preserved still worth living knowing you will now have to carry the guilt of your crime? Keep in mind such philosophical questions are much easier to answer from the outside, but even the kindest and most moral person can be twisted by pain and fear and grief. While most of the heroic sacrifices made by those the Behemoth killed were merely pointless deaths (they died horribly and all it accomplished was pushing their loved ones to commit monstrous deeds to get them back), the murdered are also the only characters in the book who get to die with a clear conscience. If there is an afterlife, they'll be the only ones joining Job in paradise.

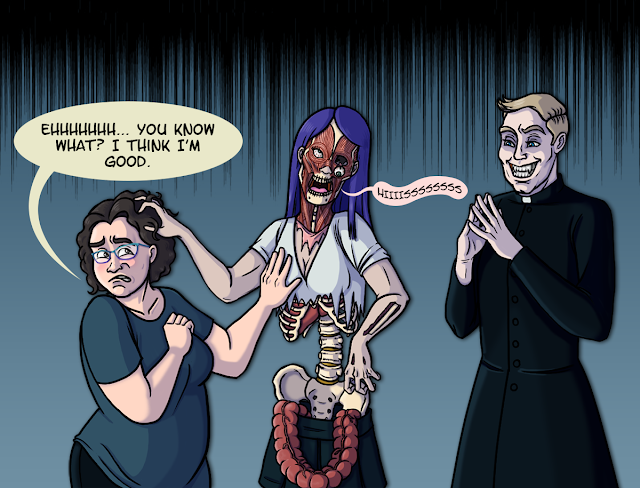

The threat of death and suffering, especially when made against your children, are certainly excellent motivators when it comes to recruiting the unwilling, though I do have to question the decision making abilities of those members of the congregation tempted by the Behemoth's promised "rewards": torture (which Rick seems to be super into) and bringing Evil Dead versions of their murdered loved ones back to life. Why bother to offer a moldy, half-eaten carrot when the stick would suffice? But while no one takes them up on their offer of some old fashioned masochism, a lot of the characters fall for the "I'm going to murder someone you love then give you this evil, busted, half-assed version instead" scam Rick and his beast buddy are running. I don't care how much you miss your kid, nobody wants a monster that makes the reanimates from Pet Sematary seem kind and cuddly by comparison, even if it does vaguely resemble a mutilated version of little Timmy. If my wife got mauled by monsters then Monkey's Paw-ed back to life looking like something out of Resident Evil, I'd be reaching for the flamethrower, not agreeing to join some prehistoric beast's weird torture church. Maybe if the Behemoth agreed to send my undead wife back to the cornfield or wherever I might agree to a little light beast worship, but as it stands his resurrection game needs some serious work.

|

| My wife as a mutilated, living corpse is definitely one of the weirder things I've drawn. I showed this drawing to her and now she's shuffling around the house pretending to be a zombie. |

***Content warning for discussion of rape and sexual assault***

Among his many newfound powers, Ricks now possesses the ability to make people sexually attracted to him, whether they want to be or not. This creepy ability is first demonstrated when a heterosexual man finds himself inexplicably lusting after Rick (right before Rick kills and mutilates him). He uses it again on Angela whilst sexually assaulting her, resulting in her arousal during the assault, and the way it's worded is pretty cringe-y:

"Her body began to revolt against every intellectual, spiritual and personal value she had tried painstakingly to uphold. This man, this creature, this demon, had violated her, beaten her, lied to her, threatened her life and the life of her child, but still her body wanted him. It ached for him, as if it would die without his touch, inside and out... She hated each and every betrayal her body made."

This is a trope I absolutely loathe with a burning passion. Let me be perfectly clear: some people do experience an erection, lubrication, or even orgasm during a sexual assault, and there's nothing unusual or shameful about it. It's a purely physiological response and not an indication of enjoyment or a sign of consent. Unfortunately, the belief that any sign of arousal means the victim "wanted it" is still prevalent (and even used as a defense in court cases) and enforced in fiction like Crown of Swords, The Fountainhead, Goldfinger, Game of Thrones, and numerous Harlequin romances. Fifty Shades of Grey actually inspired at least three different cases of sexual assault because these men couldn't understand that fantasizing about being ravished isn't the same thing as wanting to be assaulted (Pro tip: NO ONE wants to be raped). It's not that people shouldn't write about rape (The Round House by Louise Erdrich and Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson both do an excellent job dealing with such a difficult topic) or even erotic fantasies of being overpowered. It's just that with rape culture and world being what it is, authors need to tread very, very carefully when writing about assault. Tor, Apex Magazine, Wired, the Writing Reddit, and Marie Brennan's blog all do a great job discussing how to write about sexual violence in fiction.

Worship Me isn't nearly as bad as the previous examples I listed, Rick is portrayed as a complete monster whom Angela despises and what he does is reprehensible. I don't think anyone reading that passage is going to think Angela wanted him to assault her, or that it was anything but a violation. But it still could have been handled a lot better and I cringed reading it.

***End of content warning***

Problems aside, Worship Me is still a well-written, and entertaining read. You would think a book where the characters spent the majority of their time trapped within a church reflecting on their personal values would get dull very quickly, but fear not. Action scenes are perfectly placed throughout the story to keep the pace going and the tension high. Even with my ADHD, Worship Me managed to hold my attention throughout the book and I only put it down when I absolutely had to (like when my wife said if I didn't come do the dishes right now she was making me sleep in the backyard). But it's the novel's exploration of faith that makes Worship Me really stand out. I was very fortunate to grow up attending a Congregationalist church part of the United Church of Christ (UCC) with a strong emphasis on humanism, tolerance, science, and social justice, where my sexuality and agnosticism were readily accepted, but many people aren't so lucky. Even churches that aren't showing up on a Southern Poverty Law Center watch list can be intolerant towards anyone they see as breaking some obscure Biblical law from Leviticus. When a religion that's supposed to be about love and compassion is twisted by its followers into an ugly culture of hate, judgement, and hypocrisy it drives people away. But worse than that is when people actually find that kind of message appealing. They're attracted to the "us vs. the sinners" rhetoric and instead of loving their neighbors or respecting differences, they turn to condemnation and cruelty in a misguided attempt to please an angry god and reap the rewards they feel are promised them. And this is the heart of what makes Worship Me so terrifying. Not the monster outside who may or may not be an old god come to challenge the newer god of Abraham, but the horrible lengths people are driven to when they believe without question. Worship Me isn't so much anti-religion as it is anti-zealous, unquestioning belief and fear-based worship. There are benefits to religion, it can offer comfort in dark times and encourage charity and compassion and a sense of community. But when the message is never questioned and when its followers lose the ability to judge right or wrong from themselves, that's when people suffer. Churches will always make me leery. Maybe it's because some very vocal religious types find both my sexuality and my lack of faith sinful, and are not shy about harassing anyone like me. It could also be that whole bursting into flame and vomiting black bile every time I step onto holy ground thing that happens, who knows. What I do know is the Worship Me has definitely made me think twice about visiting a house of God again, lest it hold some even darker secrets.